Introduction: The Truth Behind George Washington’s Dentures

Few legends in American history are as persistent as the claim that George Washington’s dentures were made of wood. This myth has circulated for generations, shaping classroom stories and popular culture alike. Yet the reality is far more complex—and far more revealing—about the life of George Washington and his lifelong struggle with debilitating dental problems.

We examine the historical record, documented correspondence, surviving artifacts, and expert scholarship to separate myth from fact. From the materials used in his dentures to the political consequences of his dental troubles, the truth paints a vivid portrait of the first President’s enduring resilience.

Washington’s Lifelong Battle with Dental Disease

Despite his image as a symbol of strength and fortitude, Washington endured chronic dental suffering throughout his adult life. At just 24 years old, he recorded in his diary a payment of five shillings to a dentist who extracted one of his teeth. This was only the beginning.

Over the decades, Washington’s letters and account books reveal:

-

Repeated tooth extractions

-

Inflamed gums and infections

-

Ill-fitting dentures

-

Purchases of dental scrapers and cleaning tools

-

Toothache medications and dental powders

By modern standards, Washington likely suffered from severe periodontal disease. Despite meticulous oral hygiene for his era—including regular brushing—his teeth deteriorated steadily.

Were George Washington’s Dentures Made of Wood? The Definitive Answer

The enduring myth claims Washington wore wooden dentures. This is categorically false.

No surviving dental appliance attributed to Washington contains wood. Instead, his dentures were constructed from a combination of materials common in 18th-century dentistry:

-

Human teeth

-

Animal teeth (cow and horse)

-

Ivory (possibly elephant or hippopotamus)

-

Lead-tin alloy

-

Copper alloy (possibly brass)

-

Silver alloy

Why the Wooden Myth Persisted

So why the confusion?

Ivory—especially when stained by food, drink, and age—can develop a brownish tone resembling wood grain. Observers unfamiliar with the material may have assumed the dentures were carved from wood. Over time, the misconception solidified into folklore.

The Only Surviving Full Set of Washington’s Dentures

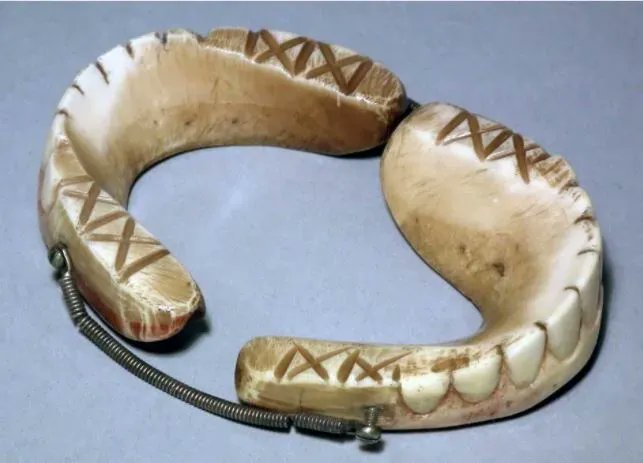

Today, the only remaining complete set of Washington’s dentures is preserved at Mount Vernon, his Virginia estate.

These dentures demonstrate remarkable craftsmanship for their time. They consist of carved ivory bases fitted with human and animal teeth, held together with metal springs designed to keep the upper and lower plates in place. The tension system was uncomfortable and required the wearer to keep his mouth clenched shut.

The dentures are temporarily off display during an exhibit renovation but are scheduled to return when the updated exhibition reopens in 2026.

Washington and Teeth from Enslaved People

One of the most sobering discoveries in Washington’s financial records is an entry documenting the purchase of nine teeth from enslaved individuals for 122 shillings.

The records do not definitively confirm whether these teeth were used in Washington’s own dentures or supplied to his dentist. However, the transaction underscores the intersection of dentistry and slavery in 18th-century America. Although payment was recorded, enslaved individuals did not possess genuine freedom to refuse such requests.

This documented purchase provides critical historical context and challenges simplified narratives about early American leadership.

The Revolutionary War and a French Dentist

In 1781, a prominent dentist named Jean-Pierre Le Mayeur defected from British-occupied New York and offered his services to the American cause.

Le Mayeur had previously treated British commander Sir Henry Clinton and other high-ranking officers. After taking offense at British insults directed toward the Franco-American alliance, he crossed into American lines and began treating Washington.

The two developed a professional relationship that continued after the war, with Le Mayeur visiting Mount Vernon frequently.

How Washington’s Dental Troubles Misled the British Army

Washington treated his dental issues as a private matter. In 1781, however, a letter requesting dental instruments was intercepted by British forces. The correspondence suggested Washington had no plans to move toward Philadelphia.

Clinton interpreted this letter as proof that American forces would remain near New York. In reality, Washington and French commander Rochambeau were preparing to march south to trap Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown.

This miscalculation contributed directly to the decisive American victory at Yorktown in October 1781. Washington’s dental secrecy inadvertently became a strategic advantage.

Retaining Extracted Teeth for Future Dentures

Aware that tooth loss was inevitable, Washington kept several extracted teeth in a locked desk drawer at Mount Vernon. In a 1782 letter, he instructed a relative to send these preserved teeth to him in New York for possible use in new dentures.

This practice was not unusual. Dentists often reused a patient’s own teeth in prosthetics when possible, as they provided better aesthetic consistency.

Dr. John Greenwood and Washington’s Final Tooth

By the time Washington was inaugurated as the first President in 1789, he had only one natural tooth remaining. That final tooth was extracted in 1796 by John Greenwood, his longtime dentist.

Greenwood later mounted the tooth in a small display case and wore it as a keepsake on his watch chain.

How Dentures Altered Washington’s Appearance

As Washington’s natural teeth disappeared, his facial structure changed significantly. Dentures of the era were bulky and required constant muscular tension.

In letters to Greenwood, Washington complained that his dentures were:

-

“Too wide and too projecting”

-

Causing his lips to bulge outward

-

Distorting the natural shape of his jaw

Portraits by Gilbert Stuart show a noticeably distended jawline in later years—an effect likely caused by ill-fitting dental appliances.

Martha Washington and Her Dentures

Even Martha Washington required dental assistance. By the 1790s, she requested a new partial denture, asking that it be made thicker and slightly longer than her previous set.

Her correspondence reveals practical awareness of dental health, and she encouraged her children and grandchildren to care diligently for their teeth—likely influenced by her husband’s suffering.

Did Dental Problems Affect Washington’s Public Speaking?

Many historians believe Washington’s dental pain reduced both his willingness and ability to speak publicly. The spring-loaded dentures required jaw pressure to remain stable, making extended speech physically demanding.

Combined with chronic discomfort, this may explain why Washington was often described as reserved in public settings. His brevity may have been partly physiological rather than purely temperamental.

The Construction of 18th-Century Dentures

Washington’s dentures were sophisticated for their time. They were built with:

-

Carved ivory bases

-

Individually set teeth

-

Gold or brass screws

-

Metal springs to maintain closure

Unlike modern dentures, they did not rely on suction or adhesives. The mechanical tension system often caused pain and jaw strain.

These devices were handcrafted, adjusted repeatedly, and required frequent maintenance.

Conclusion: The Real Story of George Washington’s Teeth

The myth of wooden dentures oversimplifies a deeply human story. The truth reveals:

-

Washington never wore wooden dentures

-

His dental appliances were made from ivory, human teeth, animal teeth, and metal alloys

-

His dental troubles shaped his appearance, speech, and even wartime strategy

-

His experiences reflect both the limitations of 18th-century medicine and the moral complexities of his era

Understanding Washington’s dental history enriches our view of the man behind the legend. It reminds us that even towering historical figures endured private struggles that shaped their public lives.

His dentures are not symbols of rustic simplicity—they are artifacts of resilience, innovation, and historical complexity.